(I wrote this, after my first brief visit to China, back in 2007, before I had a blog).

China was not part of our original itinerary but we were planning to visit Seoul and it’s just a hop, skip and a jump to Beijing. It seemed silly not to take the leap.

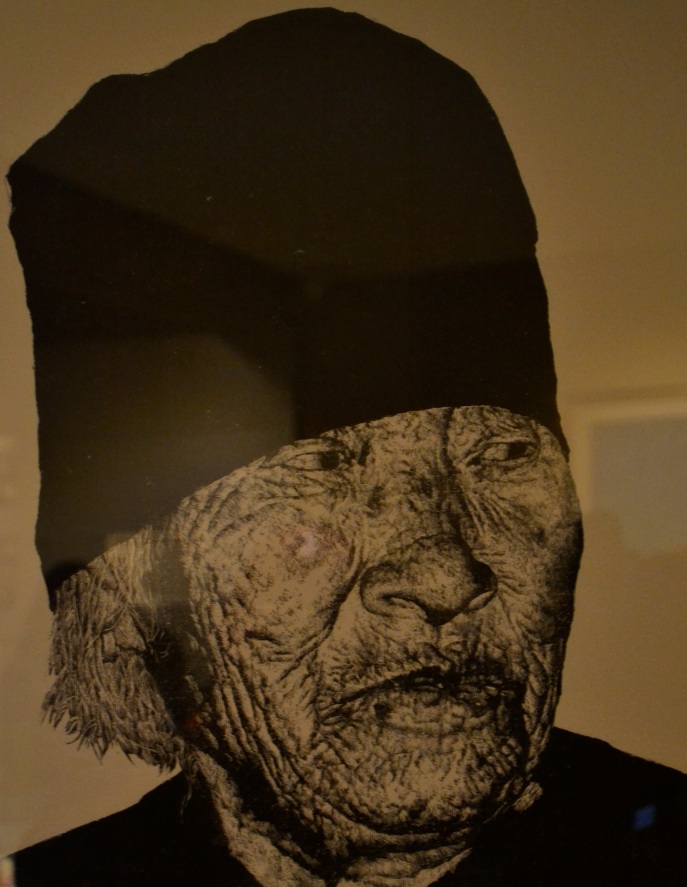

I’d imagined grey sky, smog, and a reckless juggernaut of capitalism. Well, the smog proved true, and the capitalist invasion is too. But grey, Beijing is not. All over the city are parks and carefully cultivated gardens. The Forbidden City is a riot of colour. In Tiananmen Square, Mao’s portrait looked far more benign than I’d imagined. I wanted to join the large queue moving slowly to view his embalmed body, but we didn’t have time.

They’re preparing for the Olympics with a clock counting down and in the Square there is a topiary Acropolis which will no doubt impress the Olympic tourists. What are they planning to do about the smog? It seems they will shut down the factories for three months before the Olympics and ban cars from the city. Many of the factories are owned by European car manufacturers. We heard that there were three million cars in Beijing (I don’t know who counts them) but yes, the air was more like a good meal than a mild refreshment. I’m more concerned about the athletes making it in one piece to the Olympic Stadium – you see the traffic is unforgiving and unrelenting. A green light to a pedestrian means very little to the traffic. You need either an enormous bravado (he who dares wins, or dies) or else you need to gather a large group of people with yourself in the middle, before you cross the road.

It was easy to imagine how beautiful the city would have seemed without all these cars and with people riding their bicycles dressed in their Mao pyjamas. For just a moment, I wanted to see that. But then I thought about the fate of the sparrows and the intellectuals. I asked our tour guide, Mark about his family. His father had been a schoolteacher. I questioned him about his father’s life. Mark went quiet. “So-so”, he said. And that was that. He had no wish to say any more.

Nothing in Mark’s commentary about the history of this beautiful city, mentioned what is now perceived in the west, as Mao’s reign of terror (otherwise known as … The Great Leap Forward). Everything was carefully worded to exclude any criticism. Here is a city embracing capitalism with a capital “C” and yet still somehow honouring Mao.

This is not an in-depth tour of China but more of a tourist’s overview. A highlight is our walk along the Great Wall. We’re most fortunate to be on a section of the wall with not a lot of tourists and because we are reasonably fit we manage to burn off our Chinese fan club (yes literally, they walk beside you and fan you because of the heat) and end up alone, just the two of us walking until we meet a guard with his mobile phone who prevents us from going any further, because that section of the wall is unsafe. Many (many) years ago in Form One (Intermediate School), I gave a speech to my class on The Great Wall of China. I cannot recall why I chose this topic or indeed, what I spoke of, but it is an extraordinary feeling to be actually walking on the wall, something back then that I had never imagined.

We catch the overnight train to Xian from Beijing to marvel at the Terracotta Warriors and find ourselves cycling around this beautiful walled city, almost eating the air. Yes, to quote my son after his first trip to India (a place he fell in love with) the air was as thick as wasabi on a wafer. I want to peel back the pollution to uncover this ancient city, its clouded beauty. If I cup my hands, I am certain I can catch a piece of air and hold it.

Our next stop is Shanghai, a city vivid in my imagination. My dreams are of the Bund as it had been without the spectacular high-rise development on the other side of the river (Pudong) and so I am disappointed. But we have a taste of what might have been old Shanghai in a historic teahouse looking out through a tangle of overhead wires.

It is October and we are there to witness the national celebration of the People’s Republic of China. Cars are banned from the city centre and The Bund for three nights. It truly happens, causing stress to unsuspecting tourists in mid city hotels who have planned to catch taxis to connecting flights or trains. The streets throng with Chinese (one child) families enjoying themselves – no liquor – no violence – just a swell of families and innocent pleasure – in contrast to the screaming neon along the waterfront; although they are quite beautiful too. And then on the third evening of celebrations, we look up at a clear blue sky. So, it is possible! Maybe by the time all those highly trained athletes arrive in Beijing, the air there will be clear. What will happen to all the industry that is shut down? It is hard to imagine. But noting how obedient the traffic in Shanghai is in obeying the ban, I am heartened.

Flying out of Shanghai heading towards Athens, on Lufthansa, I sit next to an enthusiastic Chinese travel agent. She is sitting in my allotted seat, but I don’t have the heart to complain, as she is so excited having just swapped seats with another travel agent to sit by the window. She confides in me this is her first overseas flight. She expresses her disappointment at the lack of “uniformity” of the Lufthansa hostesses who are all wearing similar coloured casual but not matching outfits. The meal arrives and we have to choose between hot noodles in a carton or cheese and salad on a bread roll. My new friend chooses the bread roll because she tells me she wants to try everything. She asks me, holding up her bread roll “Is this the cheese that makes you fat?” Before I can reply, she is waving to the hostess and has swapped her roll for noodles. We talk about food and waste and living in China. She tells me when she was a young girl her Mother said they must not waste a single grain of rice because if every person in China wasted one grain of rice, each day… the mountain of rice grows before my eyes. I ask about her parents and Mao, and she explains that it had not been easy for her parents growing up under Mao. At this point her voice changes, just like Mark our tour guide’s had. It’s a tone that implies that they understand but we don’t. ‘Difficult” she says, and then so I won’t get the wrong impression, she adds, “Mao meant well”.

The European car manufacturers say they mean well too, producing low-cost cars in China. I heard one such manufacturer bragging on television about how cheaply they could reproduce their brand in China.

I imagine the mountain of rice and the mountain of cars, growing side by side.