Skinship Run the sound over your tongue let it roll for a while in your mouth then swallow it whole Skinship, like kinship, meaning connection but through the skin as simple as holding hands Konglish, meaning Korean English, a new word, but not a new feeling Skin on skin, a hand in yours, a touch, skinship kinship, friendship It’s not difficult to guess why Korea created this new word Fathers holding adult son’s hands, mothers holding daughters Touching, skin on Skin, with kin this word Skinship It crosses culture it caresses skin on skin The ship of affection Skinship Sail on you beauty Daebak!

Travel

For last year’s words belong to last year’s language

StandardFor last year’s words belong to last year’s language

(Four Quartets, Little Gidding, T.S. Eliot).

I am standing somewhere in Leicester Square. It is either midnight or close to. I am inside a red phone booth. Maybe it reeks of urine, but I do not remember. In my hand is a black receiver with a mouthpiece into which I am speaking. My head is nestled into an earpiece straining to catch the words coming from 12,000 miles away. I can hear my own words echoing back at me over the voice of my mother, and then my father. Just before the three minutes is up, an operator interrupts our stilted conversation to let me know that if I wish to continue, I need to insert more coins. Three minutes is all I can afford and all it affords me, is a series of frantic hellos and goodbyes echoing into the night. It is 1972, phone calls are expensive.

Christmas that same year, I am in Edinburgh living in a neoclassical (now historic A listed) building in Leith, on the edge of respectability. My flat is dark, bitterly cold and has a bold red street facing front door. A telegram arrives to wish me Merry Christmas Stop and a Happy New Year Stop. Each word costs my parents a small fortune, the two stops included. We are not on Viber, we cannot see each other and my blue aerogrammes take a week or two to cross the dateline homewards. My Dad drinks at the local pub after work every night. He is good friends with the local postman. Sometimes, if an aerogramme has arrived before delivery the next day, the postman will take my letter and deliver it in person to my Dad at the pub.

I grew up in a modest post-war Jerry-built wooden bungalow. Ostensibly we were working-class but New Zealand was more egalitarian back then. In our street including my Dad, a carpenter, were the butcher, a baker, a painter, a chemist, a doctor, three schoolteachers, and eventually, years after I left, a Prime Minister. Most women back then were not in paid work, well not in our street. We had no telephone. If we wanted to call my grandmother we needed to walk to the top of our street, up a small hill, to a phone booth. I was born in a cottage hospital at the top of that hill. My father and I received the news of my grandmother’s death in that phone booth. My mother was with my dying grandmother. Dad and I walked up the hill to the phone booth to call for news. I recall I screamed. A man passing by in his car, heard me scream, stopped and came to rescue me – seeing me in a phone booth with my Dad, and not knowing quite what was going on. This same man, when he learned our sad news, that my grandmother had just died, drove us up to my grandmothers.

When I lived at home, I woke each morning to the sound of the BBC News, as my father washed himself in the bathroom and sang. We had a tin bath but no shower. His ablutions were a ritual of running water and a lot of sloshing. Big Ben would chime before the news over shortwave radio and the news reader had a gravitas that brooked no doubt. No one speaking in such a well-bred, carefully modulated timbre could possibly be telling other than the truth. The Cuban Crisis, Kennedy’s assassination, and his funeral, all came to us from the blue Bakelite radio above the small green fridge. The fridge I might add, was a modern wonder that had replaced but not entirely, the safe above the kitchen sink near the coal range.

My eldest brother left school to join the Merchant Navy and was travelling as a teenager to the Pacific Islands specifically Nauru for phosphate and up to Hong Kong and Japan. He returned from a trip with a portable tape recorder as a gift for me. It had a small microphone for recording and tiny reel to reel tapes. My best friend and I would visit the local shops and record our conversations with the fruiterer or the local bookshop. I would secrete the tape recorder, uncomfortably under my cardigan. I would disguise the microphone which hung around my neck with a daphne cutting from my mother’s garden. We felt like spies and thought ourselves entirely clandestine. I cannot recall any of the recordings, but I smile now to think that we thought we fooled anyone.

Many families back in the 60’s owned stylish stereograms, which appeared to be as much about furniture as about music. Some cabinets that housed the turntable also converted into a drinks cabinet. Our very first musical turntable was a wind-up gramophone and from memory, we had two records. One was Mario Lanza which may well have been quite hi-brow and the other played the Irish song The Stone Outside Dan Murphy’s Door. The gramophone was in a case that sat on the floor in the front room when it was played and then it was put away in the big cupboard in Mum and Dad’s bedroom. Unless you wound the handle sufficiently, the record would slow right down and that is my memory of the final refrain of the song which repeats the title, in a slow motion sound as the gramophone wound down. Many years later, an older sibling purchased a full-size ACME reel to reel tape recorder. We taped from the radio and had everything from Herman’s Hermits, the Beatles, Dusty Springfield, Petula Clark, Simon and Garfunkel, Sandie Shaw, Helen Shapiro, Diana Ross and Cilla Black. When I look back, we were lucky with so many outstanding female singers to listen to back then. Our influences were very much persuaded by the English pop charts early on, rather more than the American.

Then in the early 70’s, travelling by myself, I took my music with me on a small cassette player, listening to Carole King, Cat Stevens, Donovan, Neil Young and Blood Sweat and Tears, mostly American music. Later, in the mid 70’s, travelling with my now husband, we would make recordings of ourselves talking to our families on small cassettes and post these small cassette tapes home. The cassette would then be recorded over by the recipient, my husband’s brother, or my Dad, as by then my mother had died. I still recall our laughter, as we sat in a Norsk hytter surrounded by metres of snow, as my future brother-in-law back in New Zealand with a young family, regaled us with the woes of the newly instigated daylight saving. The entire one-way conversation was meticulous detail of the complications of old time and new time, the impact it was having. It made no sense to us that someone could be so disturbed by a one-hour difference in their lives. We’d just hitch-hiked to Lapland to observe the Midnight Sun. It wasn’t until we had our own family in the late 70’s and very early 80’s, that that one-hour difference when putting a toddler to bed, finally registered with us.

All my photos taken when travelling by myself in the early 70’s, including a solo Greyhound Bus trip around the USA, living in London, Newcastle, Manchester, Edinburgh and Norway, were recorded on slides. When I returned for the first time from overseas, a friend of my dear maiden aunt’s, invited me to her house along with her local friends and neighbours to show my slides. I recall how amateur my slides were, so dark and different from the instantly captured high resolution photos that an iPhone can capture. We were all in her front room, the lights out, a slide projector was whirring as photos of me in a purple midi coat standing by Cleopatras Needle on the Thames finally came into focus upon a white bed-sheet on the wall. The audience were all appreciative and I was the feted returning traveller. London, our Colonial homeland, and I had been there, although both my mother and father were born in New Zealand. Watching Helen Mirren before she was famous, at Stratford on Avon in a Royal Shakespeare production which from memory was performed outdoors by the river. But memory fails me on which particular play.

For a short time during my OE, I was staying in Nazareth Pa, USA having fallen in love with an American Coastguard sailor who had dodged the Vietnam Draft by signing up for seven years on the Icebreakers. We met at the Downtown Club in Wellington in the late 60’s and I ended up staying for some weeks with his family who were bemused by this girl from Downunder. I recall Polaroid photographs were the technology of that time, an instant image rolling out from the camera in technicolour. I kept a couple from that era, but they have faded. Then, more recently, my daughter-in-law purchased a brand-new super-duper Polaroid camera which had a brief moment in our lives, but not for very long. TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat, the list continues and images of sunsets and sunrises so ubiquitous as to be rendered schmaltzy. Everyone is a photographer, and everyone can communicate almost instantly with almost anyone in the world. We are blinded by sunsets, sunrises, and airbrushed joy.

When I returned from my travels in the mid to late 1970’s, I was employed for a while with the Time Life Magazine Sales Office in Auckland. These were heady days when triple page spreads for Rothmans or some Liquor brand, kept the magazine viable. The Sales Team at Time simply wined and dined the advertising agencies at such places as Antoine’s, Le Brie or Clichy’s ensuring ongoing advertising placements. It was a time of lavish expense accounts and too, the emergence in Auckland of trendy fine dining. Time Magazine had prestige and clout back then. Possibly a time of general naivety without the Twitter trail of fact checking. I recall an issue of Time Magazine dedicated to South East Asia when Muldoon and some sheep were on the front cover. Advertising was easy to sell with a front-page story about New Zealand. Journalists and a famous photographer, Rick Smolan, fresh from his filming of Robyn Davidson trekking across Australia on a camel, came to New Zealand for about three days. Nowadays, Robyn Davidson would be more likely instagramming her own journey on a camel. I recall Rick Smolan travelling light with a camera slung across his shoulder and the straps of the camera festooned with baggage tags. Baggage tags back then were an overt status symbol. Those of us who travelled, left the tags on our suitcases, proof of our international adventures. The photographer and a couple of Time Life journalists travelled to Taupo. They stayed at Huka Lodge and wrote romantically about Zane Grey and fishing in Lake Taupo. I saw the expense account. For the price paid, I envisaged scuba divers in the lake putting trout onto the fishing lines of the journalists… but worse than that, the statistics in the primary piece about New Zealand, specifically about child mortality were somehow grossly over misrepresented. There were other factual errors and my faith in the 4th Estate began to wane.

I recall the heady afternoon, when one of the Time Life Sales Team brought in a fax machine. It was I think 1977 and the fax didn’t really take off for everyday use commercially until the 80’s. We may well have been the very first commercial companies in New Zealand to receive a fax. A small group of us waited in the boardroom with the Sales Team, our eyes glued to a compact machine on the coffee table. A fax came through from the Time Life Sydney office. Prior to that, the communications had been by telex. Back in the sixties, when I joined the Post Office as a shorthand typist, we would use up to six carbon sheets when typing a single memorandum, so that it could be circulated around the branch office. I was also responsible on shifts, for a small switchboard answering incoming phone calls and plugging the phones in manually to the extensions required.

About ten or fifteen years ago, we rented a holiday house in the Marlborough Sounds. The house had its own private beach reached by boat from Picton. We were somewhat surprised to read the instructions left by the owner of the house regarding phone calls. The house was on a party line and we were told not to answer the phone unless it was (for example, as I no longer recall exactly), long short long. Throughout the long weekend, the phone rang and rang incessantly. It was the same number (not ours) over, and over again. Finally, in frustration, my friend answered the phone. The caller was from London and furious that we had answered the phone, thus incurring her the cost of the call. She did, however, stop phoning, thank goodness, as it seemed obvious to all of us that whomever she was calling was not at home that weekend.

I contrast all of this with my solo adventures around the USA in 1972, doing a Greyhound bus trip from Vancouver Canada down the West Coast and up the East Coast including forays to Las Vegas (in those days, merely a strip and a few pokie machines). I even naively and yet safely, hitch-hiked on several occasions. Thankfully, my mother and father back in New Zealand, knew nothing of my adventures, apart from postcards that probably arrived, long after any perilous adventures. Too, there were broken hearts that I healed by myself, without recourse to instant contact with close friends and family back in New Zealand. My adventures were frequently about romance and idealised love, and I am glad in retrospect to have had these challenges to myself, made mistakes that only I know of, and poured my heart out into a diary, from which several pages have been torn and destroyed. The short few weeks when I was certain I was pregnant after unprotected sex. My mother back in New Zealand didn’t need to know and I had no one to tell. When I bled, it was a great relief. I’m glad I wasn’t in daily contact with my mother during these times. Too, when I ended up at the clinic for sexually transmitted diseases after my first sexual experience. This was a solo adventure, the penicillin worked and to be honest I was mortally ashamed. I imagine nowdays, that it might even be Twitter worthy news. That same first experience spawned a successful poem, fifty years later.

I’m on Twitter nowadays and mostly for the political links that I find. I’m fascinated by the banal, trivial and outright nasty comments that people I admire are prepared to post. Most recently Neil Gaman and his partner Amanda Palmer, stranded here in New Zealand during lockdown, enacted the early stages of a relationship breakdown, live on Twitter. My thoughts were for the innocent child in the middle of this so very personal muddle. Oh, I judged them, I did, but I could see that most people responded with empathy and compassion. And as happens on Twitter, many took sides, alas. It all seemed odd to be washing their laundry in public as my mother might have said.

I compare the use of Twitter and contrast this with the gravitas of the BBC News on shortwave radio. At least now I can verify facts, double check with several sources and make informed decisions. So I’m not wishing to go back to a time of censorship. A time when I idolised JFK and Jackie Kennedy and knew nothing really of American Politics. A time when I loved the Royal Family and went eight miles on the suburban bus to the picture theatre to watch the film of Princes Margaret’s wedding. Innocence indeed, and we also stood at the local Picture Theatre for God Save the Queen. A few dissidents in the more expensive seats at the back, often protested by sitting down, but we kids in the cheap front three rows knew nothing of politics. We were in thrall to the Metro Goldwyn Mayer’s and Paramount Pictures. Enchanted by the raising of the rich velvet scallop shaped curtain as it rose from the stage to expose the white screen. Billy Vaughan’s Sail Along Silvery Moon can still transport me to the magic of the Saturday Matinee, a sense of wonder. Yet nowadays I’m more likely to watch foreign films and arthouse movies than blockbuster Hollywood releases.

I started work as a sixteen-year-old at the Post Office, working on an Imperial 66 manual typewriter pounding the keys with up to five or six carbon copies. And today I write this essay from my brain to the screen on a Surface Pro that is so light, I carry it like a clutch bag. My travel in the 70’s was not documented on Instagram or Facebook. I have barely any photographic record of this adventure and instead I must retrieve these memories from my own internal memory bank without Facebook to prompt me, or photos from my phone. I can switch screens to check Facebook, check my phone for updates from Radio New Zealand about Covid-19 cases, use Google to verify the spelling of Rick Smolan the famous photographer I met briefly in 1977 and return with ease to place my thoughts on a screen that allows me to justify, spellcheck, delete and importantly to ‘save’, ready for emailing my entry to the Landfall Essay Competition. No doubt Instagram will remind me of the looming deadline.

Lockdown Villanelle

StandardLockdown Villanelle

(for Emma Aroha)

In lockdown she learned to wish the moon goodnight

Muddling two languages to make a new word for water

I learned to say pada and she knew it was the sea

Bashing back the Spinifex dodging spikey grasses

Chasing seagulls in circles on freshly wet sand

In lockdown she learned to wish the moon goodnight

Nana is my Kiwi name, in Korea I’m Halmoni

We talked to stars together, marvelled at the moon

I learned to say pada and she knew it was the sea

We inspected dying jellyfish followed scuttling crabs

New words emerged, that neither of us understood

In lockdown she learned to wish the moon goodnight

We ate lunches purchased from the local bakery

I discovered strawberries are also called ttalgi

I learned to say pada and she knew it was the sea

Some days we walked and talked to teddies

In the trees, on windowsills, all unexpectedly

I lifted her to wave to them her new-found friends

In lockdown she learned to wish the moon goodnight

I learned to say pada and she knew it was the sea

Ride like a local

Standard

I walk my granddaughter

up the hill to Daycare

over grates, cigarette butts

past plastic trash bags

she finds the asphalt

mesmerising, examines

every glinting thing

with perfect purpose

We wave to the lady with

the dog wearing boots

on all four paws and she

stops and waves back

people respond to a one

year old who cares that much

about them and they break

into wide happy smiles

Later on, I board the bus and

become angry at the teenager

head down on his phone

in the seat for the elderly

I shame this young man

when someone even older

than I am, boards, but all

I do is shame myself

the old woman doesn’t

want this young man’s seat

she’d rather stand than

lose her dignity to rage

At the pedestrian crossing

I am the only one fuming

as a man in a white sedan

edges over the painted lines

I swear at him, actually

out loud but no one hears

or cares least of all him

as he roars to the next lights

As a visitor in this city

I am the elderly anomaly

carrying the luggage of

my own petty prejudice

I’m learning to contain my

expectations of others, to

tilt my parasol to the sun

ride the bus like a local

an eye out for the glinting

Daughters of Messene

StandardDaughters of Messene (now in translation and for sale in Greece)

I’ve talked about this before. The tricky balance between self-promotion and total modesty. As a writer, total modesty probably no longer does the trick. It’s a shame. It would be amazing if our work stood on its own merit. And indeed, it should. But it also needs a little push/shove along. The trouble is, if you shout too often, people become averse to your shouting. And if you don’t shout out at all, your writing achievements (however modest in the scheme of things) may not reach all their possible audience.

So, here I am to bask once more in the glow and delight of having my third novel, a story with a strong Greek flavour, that sprang out from a not very well known true story of the migration of young Greek women to New Zealand in the sixties… now translated and on sale in Greece through Kedros Publishers Athens (to whom I am most grateful).

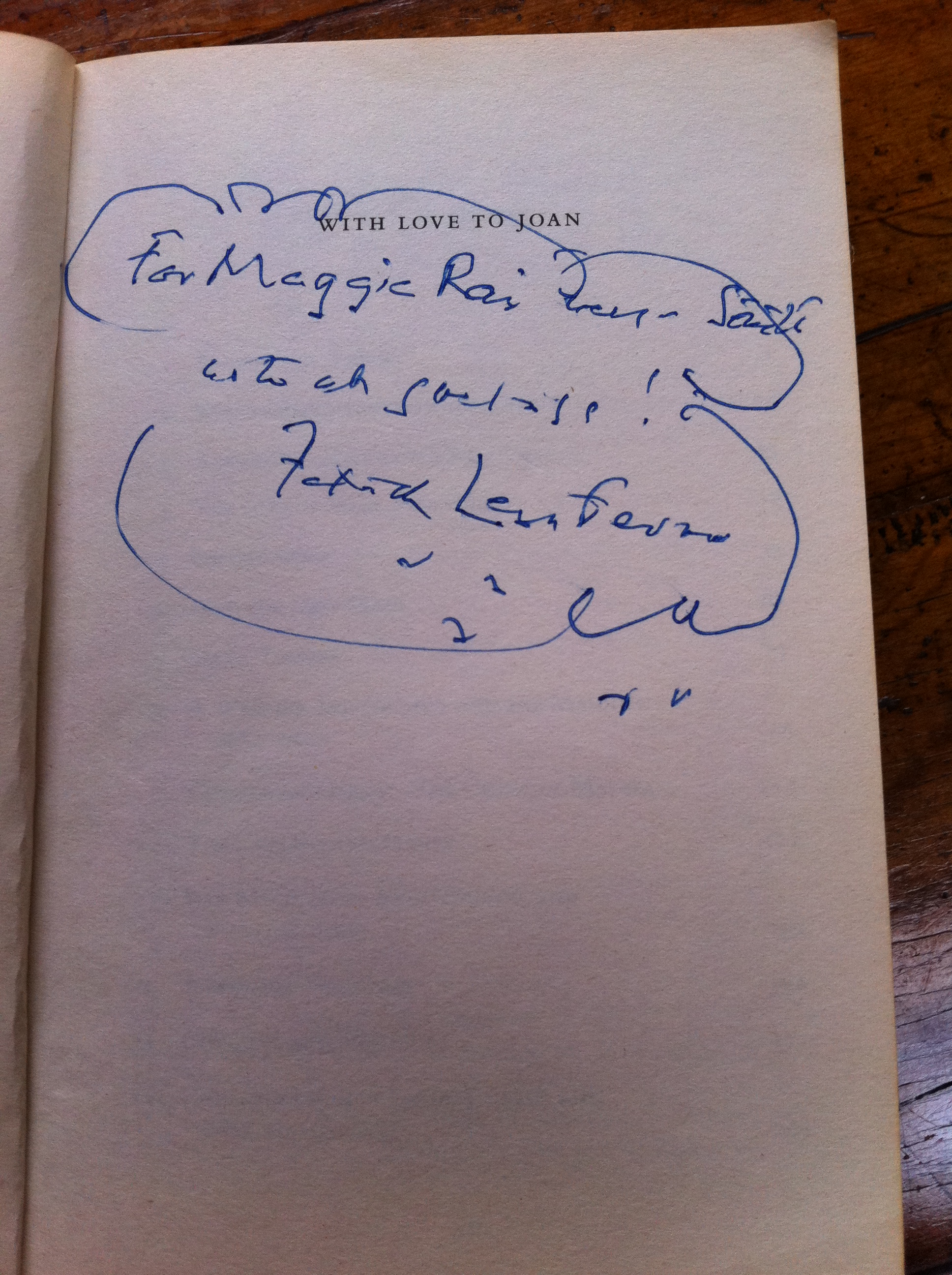

One of the lovely serendipitous moments researching this novel in 2007, I have written about before. It was my lucky encounter with Sir Patrick Leigh Fermor at his splendid home in the Mani on his Name Day. To be there, with the ‘local’s and to share this magical moment, was unforgettable. On that day, Sir Patrick Leigh Fermor, generously signed my copy of his book Mani: Travels in the Southern Peloponnese. I had found and read the book while in Greece and was bedazzled by his magical flights of language and historical observations, the marvellous segues. He signed my copy of his book with his usual motif of a small flock of flying birds.

A reader of my blog, Diana Wright, managed to decipher the inscription as I was unable to. It says ‘with all goodness’.

To my great delight, the cover for the Greek translation of ‘Daughters of Messene’ includes a similar flock of birds. This is pure coincidence and a lovely one at that. Indeed, my novel includes a moment of migrating birds, so these links are quite perfect.

So, here is the very splendid cover for you to admire and hopefully if you speak and read Greek to tempt you to buy the book. Plus a picture of Sir Patrick Leigh Fermor’s inscription in my copy of his book.

I am a Halmoni

StandardWe are walking from their apartment. Up a steep street in the sweltering heat. She is due. Her stomach is wide, round, the baby’s head engaged. Food couriers whizz by with chicken dishes for locals. We find an allotment behind a school, in a valley, overlooked by the mountains and power lines. None of us knew it was here. There is clover to entice the bees, tomatoes staked and beans already sprouting. We talk about bringing the compost here to share.

We can bring baby here when she is born, I say. Her mother is both excited and a little frightened. I grew up she tells me in the countryside, but you know, we didn’t have bugs and things. I lived in an apartment. She waves away what might be a sand-fly or mosquito, but possibly her imagination. We speak of the labour to come. Our language inhibits us. Instead, we breathe together. Breathing we agree will help the baby to arrive. I’m not sure she is convinced.

I am a Halmoni, the Korean word for grandmother. This baby is not my first grandchild. The other granddaughter lives in New Zealand and she will turn 11, just a week or so after this baby is born. I am reminded of her birth, of my love for her and of my own journey as a young mother, without a mother.

Here in Korea, the mother is mothered. My daughter-in-law is well supported. We have travelled from New Zealand to be here for four months, to be helpful. I’ve taken leave from my paid job. Her own mother is also a working woman and spends the weekends making nutritious food for a feeding mother. Seaweed soup, chicken porridge, foods that comfort as well as contribute. I am out of my depth. My daughter-in-law craves the food of her childhood. I can make chicken soup with a fresh chicken from the market. But there are family recipes and rituals I can never replicate.

So, I bring my love in my suitcase. I haven’t changed a baby’s nappy, since the father of this child was a baby. Before this baby arrives, the parents have invested in cloth nappies. We nodded in approval. Now that baby is here, we are using disposables. I cry a little with the emotion of being trusted with this new day-old baby, although my son ensures I know how to hold her fragile head. He checks, initially, whenever he passes his daughter to me, that I understand the way to hold her. And then he is back at work, and I am trusted with her lovely head.

Memories of being a new mother emerge in vignettes. I try not to say too often to the baby’s grandfather who is here with me… remember how often you were away. I recall our farm holiday near the Coast. The clothesline strung from one wooden prop to another. Cows roamed beneath. When the line was full, it collapsed, and the nappies fell in the cow pads. We had crayfish though, undersized crayfish, that the farmer gave us to eat.

At night, I recall the mishaps. The window that fell on my eldest son when he was 18 months old. He still has the scar. His wife finds it attractive. I can still see the million pieces of glass, the blood on the floor, the blood on me, and my pregnant belly. I remember the rush to the hospital in a neighbour’s car (because you were at work darling). And the night our youngest lad’s foreskin became a tourniquet around his penis due to an infection and at midnight I phoned my neighbour for help (because you were away darling…). He reminds me, this besotted grandfather, that he was trying to pay the mortgage. And we both agree, it’s much of a blur. These vignettes come unbidden, to remind us, who we once were. Brief recollections, possibly inaccurate, all follies forgiven.

Back home, my other granddaughter sends me messages on Kakao, using filters on messenger and I can’t work out how to do the same. She is wearing a cat nose with whiskers and making funny noises. I think she likes her new cousin, so I keep sending her photographs. Her mother is strict about phone contact, so all my messages are filtered through her mother. And she is right to do this. Still… I dream of the day when we will chat back and forth freely, unfiltered, to see what sort of conversation we might have.

I am her cooking granny. She learned to crack eggs (all eight of them when she was three). Sitting on our kitchen bench, making scrambled eggs. She had no fear. Cracking the eggs in one go. And quickly she learned how to separate the yolks using the open palm of her hand. Watching the albumen slide from her fingers, the yoke intact. We moved from scrambled eggs to pikelets, to buttermilk pancakes. We made faces in the pan, flipped pancakes, wasted mixture, licked the spoons and drank the melted butter. I didn’t change her nappy, because I wasn’t needed. At the time it felt like rejection, but her mother had a mother. And I’ve learned as a mother-in-law, to adjust my expectations. It’s a wise woman who learns to adjust her expectations in life. Where once I saw loss, I know love.

I’m recalling how it was as a young mother, with no mother. At the time, I was so absorbed in mothering I didn’t miss her. Our babies survive our good intentions. It is only now that I grieve, as a grandmother, wishing I’d known my own mother more. Wishing I could ask about her mothering of me. She was often unwell and had four babies, one after the other – my two eldest siblings only 11 months apart, and then a baby that was ‘removed’ for health reasons (a polite euphemism of its time…) leaving room for me. I know my older two siblings spent time in foster homes and a local orphanage run by nuns, when my mother spent periods in hospital. I’ve no idea where I was? I wonder now. Was I picked up and held by strangers, or by my mother? There is no one to ask. I feel sympathy for my mother. That I never bothered to enquire. To ask her how it was for her.

Now, I am needed. The mother of my Korean daughter-in-law is a working woman. I have taken leave from my job to come and be a Halmoni. I worried at first that I would no longer know what to do. But rocking from one foot to another and patting a baby’s back and bum is instinctive. But too, I have learned, with all my love and patience, there is nothing, absolutely nothing, but a mother, that matters to a new baby. I watch with admiration, the bond, the commitment, the patient learning as this new baby teaches her new mama, that she, this tiny infant is really the one in charge, the schedule is hers, and the sweet surrender of mother to child is a revelation. This is what we do as mothers. We surrender.

I remember my closest friend when my babies were small. She had a daughter who was between the age of my two lads. We shared coffees, recipes, babysat, and supported one another. Our children shared bath times and bedtimes. She became my rock. She too was a motherless mother. We were motherless mothers, doing our best. My friend died aged 40 from a brain tumour, leaving her 11-year-old daughter motherless. I recall her last days, the determination not to die. The fluids she drank to keep hydrated, as her breath came, it seemed, minutes apart, each breath, a wish to live longer. A wish to never leave her daughter. It still breaks my heart, and I try not to ever imagine my granddaughters motherless.

My newest granddaughter is giving involuntary smiles that some people call wind. She is opening her eyes and responding to sounds. I lean in towards her, put my face up close, dare to kiss her on the cheek, just briefly, not wanting to impose, but impossible to resist. I watch her feet as they kick the swaddle cloth off, and her hands in cotton mittens find her mouth briefly, but perhaps I am exaggerating, it’s too early, she’s only three weeks old. Her father no longer worries quite so much about her head, because her neck is strong, and she can push herself away from my shoulder as I burp her. My daughter-in-law can write burp in English and we chuckle together, waiting for the sound.

I used to worry that I wouldn’t see my babies grow to men, when my friend died. And now I grieve for the women these granddaughters will be that I might never see. I am a Halmoni.

E-bikes and bad days

StandardWe were away for the mid-term holidays. Just a short break, across the hill. Part of the plan was to hire a couple of electric bikes to try them out. The weather permitted, and we had a fun afternoon enjoying the newly found benefits of a bike set on eco, normal, or high, whereby, although you pedal, there’s a little engine kicking in to assist. I climbed my first hill on eco and was still puffing, so from then on, it was high uphill all the way, almost coasting. We smelled the cow pats, breathed in the pollen, and faced the headwinds with ease.

On our return to base, at a pretty modern cottage, in a reasonably high-end resort (special deal for mid-weekers), we collapsed, each with a glass of wine, to read and relax. I was inside, as the wind had come up and John sat outside to catch the late afternoon rays of light.

Later that evening, he told me what he overheard, while sitting sipping wine in the sun. Across from us, almost obscured by a beautifully manicured hedge, were other pretty wooden cottages. John heard a man knocking loudly on a neighbouring cottage door. The door was answered by another man who was regaled with loud apologies. It seemed the man knocking on the door wanted to apologise for having abused his neighbour in their adjoining courtyards just a moment ago. He was speaking loudly and apologetically and trying to explain that he’d just had the ‘worst day of his life’. John said, he could hear the pleading in the man’s voice and sensed him wanting the other chap to at least ask, what the matter was. But it seemed the man who had been abused, although grateful for the apology, didn’t wish to dally and enquire as to why. (Understandably probably).

John and I talked about this encounter and whether we should go and ask after this stranger, so distraught that he was abusing other people and then apologetic, saying he’d just had the worst day of his life. We speculated that perhaps his wife or partner had left him, that perhaps someone had died…. We even briefly permitted the idea of murder in the benign cottage across the manicured hedge.

But still, it wasn’t our business, really was it? And we both agreed, if we’d been closer to the encounter, it would have been okay to at least ask this distraught man if he was okay – but by the time we talked about it, it was too late really and we couldn’t be sure exactly which cottage he had come from.

And then, I looked at the date which was 12 October and that almost 50 years ago, in 1969, my eldest brother took his own life on this exact day – back then, indeed, it was the worst day of my life. I wrote a poem about this which is due out later this year in a new literary magazine Geometry. The idea that people put their heads down when others are in trouble, or when the trouble is too awful to acknowledge. Back in the 60’s suicide held a certain social stigma, and people preferred to pretend it hadn’t happened. We’re both hoping the distraught man who abused his neighbour in the resort over the hill, is okay.

Is it Fiction?

StandardIs it Fiction?

I was confronted with an extract from my second novel recently. The husband of an old friend who recently died, had just read my novel. He noticed a cameo appearance by his wife. We were out to dinner and he presented me with the extract, photocopied onto a plain piece of paper. Alone it stood, a piece of fiction, and he had a quibble with but one word. I’d used the word ‘hefty’. She wasn’t hefty, he said with a touch of regret or perhaps chastisement. He looked across at someone else at the table who knew my friend better than me, almost as well as he. She wasn’t hefty, was she, he asked again? No, she wasn’t hefty, and for a moment I had to interrogate myself as a friend, and then as a writer.

What had I done? I’d written about a femme fatale, a woman who fitted physically (apart from hefty) the deceased wife. I’d also used her Baltic State ethnic origin, so that if you knew her, which most of my readers would not have, you would have known who it was. The thing is, I was using my friend to disguise a completely different woman, who once again none of my readers would have known. Indeed, a woman I barely knew myself, but not wishing to use a ‘real’ person, I’d stolen the character and looks (apart from hefty), of an old friend… not ever thinking I’d be held to account.

And there it was, more than ten years after my novel was published, the paragraph or two (a cameo character only), was placed before me, not accusingly as you might think, but with great delight and recognition. But I was being held to account. She wasn’t hefty.

How to clarify that I was using my friend, to disguise a woman I hardly knew, to create a fictional character? Better still, my cameo character’s name seemed far from the name of either my friend or the woman I hardly knew. But that didn’t matter. Her bereaved husband, decided, that the name was close to the spelling of his wife’s name backwards. And I looked, and wondered, and perhaps it was… maybe inadvertently I’d done this, without realising. But my memory tells me that I simply googled the Baltic State country my friend had originated from and looked at possible names… attempting to disassociate the actual from the fictional.

The good news is that I haven’t offended anyone, as my friend’s husband loves this description of his wife. The scenario in which she appears is entirely fictional I say. But I realise this isn’t entirely true. It is an event that I have recreated, fictionalised, and reimagined, giving it more weight and intrigue than there ever was in the actual. But the truth is, his wife wasn’t part of this event. Why this event stayed in my mind from the 1970’s until the new millennium and emerged as a fictional truth, I’ve no idea. But it has reminded me of my first novel, when a neighbour told another friend after reading my novel ‘well, that never happened’… the thing that never happened, was me the author having an illicit sexual encounter with the neighbour… It seemed hilarious at the time, that the neighbour assumed my protagonist was indeed, myself, the author and another character was… goodness me… himself. But too, I know an old school friend wrote to my publisher after my first novel came out to say he knew me and many of the characters (oh goodness me) in my novel. Err… what to say.

After the publication of my third novel ‘Daughters of Messene’, I was stopped in the street by a neighbour who told me ‘I’ve just read your book.’ It was said in an ambiguous tone that implied ‘can you believe it, both that I’ve read your book and that you’ve written one’. And then the best part. ‘I couldn’t find you anywhere in the novel… you really are a good writer.’

I’ll take the compliment and be glad that he hadn’t found his wife, or himself…

Our very own Jurassic Park

StandardWe’ve been talking about the Catlins now for many years. It’s become that mythical place down south, that others have visited. They have regaled us with their journeys, marvelled, and mentioned the rogue waves at Cathedral Caves. How the water rose suddenly, possibly waist height or perhaps they or I have exaggerated this. But still, the Catlins sounded wild, other, and we kept promising ourselves to go there.

Back in 2005, we got close. We flew to Invercargill and grouped at Tuatapere to set off on the Humpridge Track. A luxury walk, with a helicopter carrying our luggage aloft, dangling from the craft in a large net-like basket. A celebrity accompanied each group and our celebrity was so low level that none of us had heard of him before, and I still can’t recall his name.

But, this Easter after our usual mulled wine and home-made hot cross bun festivities on Good Friday…

… we finally flew south to Dunedin enroute to the Catlins.

I caught up with an old school friend whom I hadn’t seen since Form II (the sixties and now we are both in our sixties). John indulged this re-connection made possible through Facebook initially. My friend has become a talented artist and somewhat of a recluse.

Dunedin was cold and chilly but the railway station was a revelation. Such splendour and beauty and we’ve promised ourselves to return and take the Taieri Gorge train trip someday.

We set off in our sweetly named Tivoli hire car. John who’s had a love affair with cars over many years, conceded that this compact, toy-like vehicle was actually a great machine with all the digital accoutrements that our cliched Subaru Outback lacks. We listened to podcasts as we headed to the Coast.

At first, approaching Nugget Point, I was underwhelmed, comparing it to Kaikoura and Cape Foulwind, claiming they were more spectacular… but then we climbed up to the Lighthouse and looked out at the expanse of sea and coastline in all its glory. I scanned the water prayerfully, hoping to see a whale, held my breath, wishing it into existence. No whales, but the water mesmerised. I have this weird issue that I suffer silently whenever I’m on high cliffs or looking into any kind of chasm or abyss… my brain tells me to jump and it’s not a death wish, it’s a weird and strange thing I’ve endured all my life. I know that I won’t jump but still this little battle ensues in my head and sometimes I have to just step back, close my eyes and gather my breath, alter my thought patterns.

John oblivious with his camera is always teetering at the edge, taking risks to capture the best photo, so I’ve learned to stop watching him.

We stayed at Owaka the first night and what hospitality. Our motel was mainstream budget with a room next to the laundry so we could hear the hum and throb of the other occupants washing. We had a goat tethered outside our front sliding glass door, eating the shrubs and sheep grazing out another window. We walked that night to the Lumberjack café. There was a warm fire to greet us, friendly staff and one of the nicest meals ever – John had steak and I had a lamb rump – maybe it was the proximity to the grown food, or just the expertise of the chef, but the food was mouth-wateringly good.

We walked home to the smell of coal fires and a clear sky, reminding me of my 50’s childhood. Under the canopy of the Milky Way we watched for falling stars and texted a friend in Niue to find to our surprise that it was the day before over there.

I took a quick snap of the teapot museum as we were leaving Owaka and we hit the trail for Cathedral Caves. Ever the dramatist I had concerns about us being trapped by the tide. Instead we had the most beautiful sunlit morning and easy access both in and out of the caves. A small posse of tourists got caught just after we left, as a rogue wave stranded them on rocks, but they loved that. The great beauty of these caves is their natural un-enhanced beauty, unlike the neon-lit caves we visited at Halong Bay a few years ago in Vietnam.

Then it was onwards to Curio Bay. I have memories from a marching trip in the sixties, being on the train, heading to Invercargill and we looked out the window at what we were told was the ‘Petrified Forest’, so I had images of upright trees, etched into my brain, ghostly, devoid of foliage, but standing. Everyone I tell this story to shakes their head in disbelief and tells me I got it wrong. And they are right. The Petrified Forest at Curio Bay is our very own Jurassic Park but very different from this memory etched image in my brain and indeed, the train did not run anywhere near this piece of Coast (or so they tell me). The forest was washed by the tide over 180 million years ago. It’s impossible to take in or truly imagine. John was once again lost in his photo lens stooping to capture the petrified markings on the trees.

I think of Ancient Messini in Kalamata and how we marvelled at the uncoverings, but these petrified trees are unimaginably older. I still can’t believe that tourists have free access to wander at will, and too, there are the nesting yellow-eyed penguins (we didn’t see any wildlife, and we’ve been told that late April is too late in the season). So, we may need to return.

After Curio Bay, we at lunch at Niagara Falls Café, housed in an old school building in a charming bucolic setting. The café is run by a family whose daughter is a medal winning Para Olympian and her medals are there on show, casually amid the food cabinets and bric-a-brac – no high security required for such precious memorabilia.

We spend the night in an overly spacious (expensive, but all that was available), four bedroomed house right on the peaceful harbour at a place called Waikava Harbour View, and yet the settlement is called Wakawa, the discrepancy we couldn’t quite fathom.

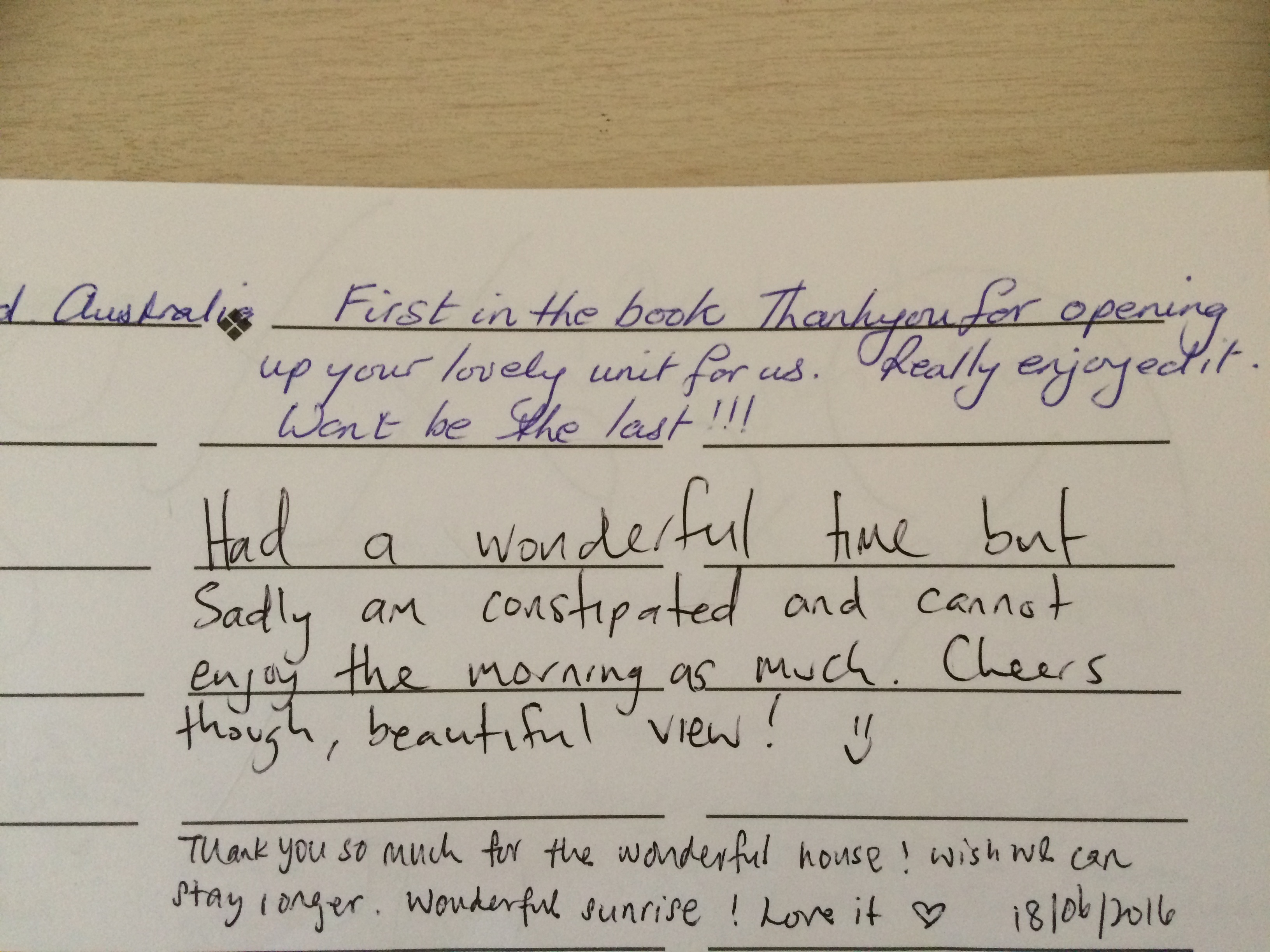

The promised Wi-Fi didn’t eventuate and here are two brilliant comments from guests which caught my fancy! You gotta love the Visitors’ book.

In the morning, after a very comfortable stay, we packed up, put our suitcases in the car and then returned to sit and enjoy the view and sunshine, only to be disturbed by a local coming, we think, to clean the house… she stood at the door, tapping her watch saying, ‘What’s the story – you’re supposed to be gone by 10.’

Like naughty school children we scuttled to the car and fell about laughing in the car at having been scolded so old-school style.

Naked in Tokyo

StandardIt was our first trip to Japan this September. We had planned a trip back on 2011 but the tsunami hit and we felt it was wrong to be a tourist in a country so stricken. On that occasion we made a detour to Cuba, a rather lengthy detour, but unforgettable.

But, the time had come. We were visiting our son in Seoul and Japan is a near neighbour, so it was long overdue. We had ten days which is not long, but long enough to plan an exciting and eventful time. Hubby plotted our course, booked the bullet trains and we managed to cram in Tokyo, Nikko (home of the three wise monkeys), Hiroshima and Kyoto (a highlight).

In Tokyo we tried to do everything that we’d read about. Hubby got up at 4 am to ‘do’ the famous fish market. He left me sleeping and grabbed a cab. Shortly after I had snibbed the lock on the hotel door and fallen into a deep sleep, he returned with a crash and a bang, trying to break down the door. Alas, only the first 100 people who turn up on time are admitted to the market. In spite of his early (as he thought) departure for this event, it wasn’t early enough – it was a Saturday and everyone was there waiting – no bribes taken – just the first 100 in the queue.

We conquered the metro. How easy it is with both the Japanese scripts plural (goodness, and I tell my ESOL students English is difficult) and the English equivalent, easily read and understood. Not only is the metro fast and efficient, it is startlingly clean. We found the Shibuya Crossing made famous by the movie ‘Lost in Translation’. It was fun to cross with all the crazy tourists now perpetuating the myth or reality of this crossing being the busiest on the planet. I have to say, a week or so later, I was in Hongdae and Insadong over Chuseok, in Korea and I’m certain both places were even more crowded that the Shibuya Crossing.

We then, naturally, had to watch a rerun of ‘Lost in Translation’ and to our dismay, saw just how racist and jaded the movie appears, in retrospect. The Japanese characters have stereotypical bit-parts and Tokyo, the city itself doesn’t get to really flaunt its stuff enough.

I was dead keen to see the crazy fashion on Harajuku Street but alas, although we trawled the side streets and followed our map, the extreme street fashion I was hoping to photograph didn’t eventuate. Too we visited the National Museum and I was most eager to view the netsuke collection (having read the memoir of Edmund de Waal ‘The Hare with Amber Eyes’).

All this is leading to telling you about my being naked in Tokyo. I’ve always wanted to go to a public bathhouse and naturally Japan seemed like the best place to do this. We read up about the various bath houses and found one on our on-line Lonely Planet guide. It was in a rather ugly shopping mall but we were told to overlook this, because it was a really good bathhouse, the perfect place to experience Onsen.

And it was. Hubby went one way and I went the other. Into the public bathhouse. It was the first time I’ve been naked in public among so many strangers and yet it was simply the loveliest most normal and beautiful thing. What a pity I had to wait until I was in my sixties to experience this.

I might well have been the only non-local, but I can’t confirm this, as once you are there, and naked there is an extraordinary kind of privacy that pervades. I was surrounded by absolute beauty. I will confess to initial shyness and discomfort. This led to me entering the main bathhouse and heading straight towards a small shallow pool in the shape of a semi-circle above which was a TV screen. I headed there because it was empty of people and sat down. It was very shallow and it wasn’t long before I realised I was sitting in a foot bathing pool. Alone, self-conscious, I began to giggle. I looked over at the big pools where the grown-ups were and I lifted myself with dignity from the paddling pool crossed the wet stone floor and descended a ladder into a deep bath with water jets and serious bathers, some chatting, some just luxuriating and one person seriously washing with great care.

I saw what looked like perhaps a grandmother with her granddaughter, young women in their teens, older woman like myself, the whole cross spectrum of naked female beauty in all its dignified glory. But the thing that struck me most was the absolute lack of self-consciousness and complete naturalness in nudity. I compared it to my preconceived ideas of say a nudist camp with mixed genders, which to me seems a bit comedic. Instead, this felt like a celebration of womanhood. I hesitate to add this, but bush was in abundance, beautiful undressed womanhood. No tattoos or piercings are allowed. I wonder if that will change with time, but without being judgmental, I kind of liked the idea. Both my sons have tattoos, so they would be turned away.

Now I’m back home in New Zealand and I’ve thought about what it would be like to go to a local bathhouse here in my own community. I feel all the old barriers rising to tell me it would be awful, embarrassing, and uncomfortable. I wonder was it because I was anonymously naked in Japan that I felt so comfortable, and that no one knew me, or was there some ancient ritual that the bathhouse routines have rendered into the atmosphere, changing what would normally be a socially uncomfortable experience for me, into something very beautiful.