The Milford Milestones

Queenstown in November sunshine – it isn’t over-crowded and the famous granite backdrop hovers, rather than imposes. All the decisions have been made prior to arrival, the tramp is pre-booked, the motel organised and all we have to do is choose a restaurant that suits all of us. It is my sixtieth birthday, and I fancy sushi, but we are sharing our holiday with a serious carnivore who craves steak – a compromise is struck – a low-key looking fish restaurant that serves the sweetest whitebait. The place is full and unpretentious and we’re glad.

Earlier in the evening, we had congregated to watch a film on the Milford Track and to cast an eye over our fellow travellers. We learned that five kilograms was about as much as we should dare to carry and watched as people rushed to buy Icebreaker t-shirts, that one extra layer in a colour they really liked, just in case. My friend found a shade of mauve that suited her.

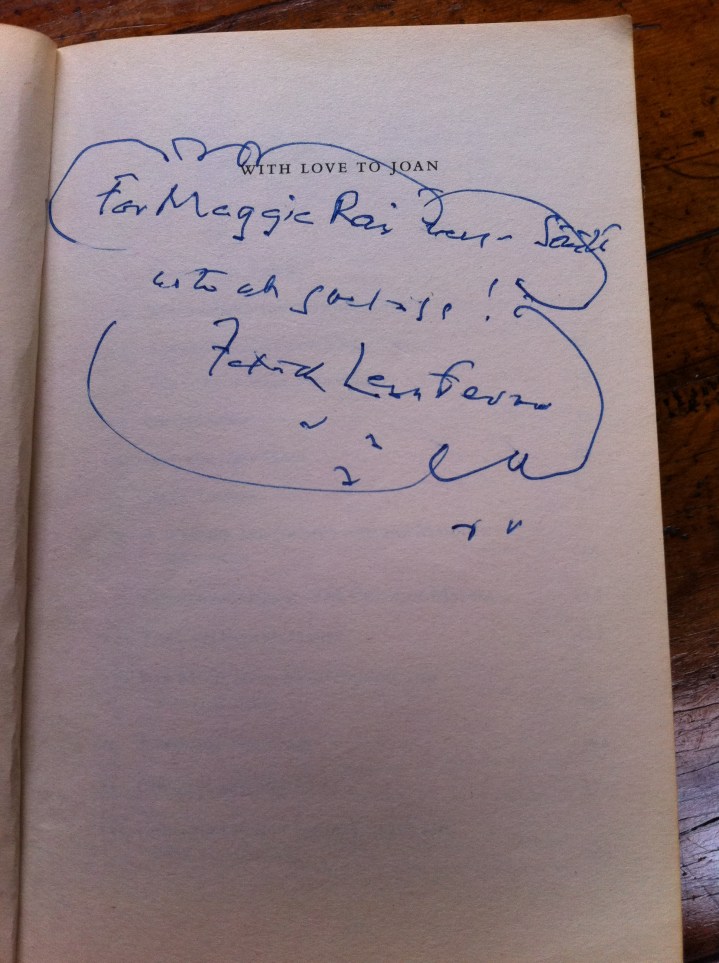

We are four in a group of over thirty and apart from ourselves and three of the four guides born in New Zealand, nearly all of the rest of our group are from overseas. It seems that most true-blue Kiwis are freedom walkers and less inclined to lash out on the ‘luxury’ version of the Milford Track. Or so it appears to me, as people scoff when I talk of my journey… “Oh, you did it the easy way.” I’ve stopped trying to correct them and their view of me, by complaining how heavy my pack was (not to mention the book I carried that I was reading to review).

And ever since, on re-reading my review, I feel a bit guilty as I preface the review by mentioning that I kept falling asleep in the first chapter. Unfortunately, I forgot to say that this was due to exhaustion from the walk, and not the fault of the novel.So, perhaps I’m not your average Kiwi tramper but of the four of us in our group, one of us is the sort of chap who goes bush in Fiordland at least once a year armed with a GPS and an inflatable kayak and he has paddled on lakes and tarns barely mentioned on maps. If he was happy to do the ‘luxury’ walk with us, then I can’t see what all the eye-rolls are about.

The beginning of the journey is sedate, with a scenic bus ride along the arm of Wakatipu with a laconic running commentary from the bus driver, translated immediately by one of our guides for the eight or so Japanese in the group. Each time she begins her version of an anecdote or description, I tried to imagine how closely, accurately she is translating, and worry too, because mostly we are already beyond the particular feature or moment that requires the translation.

We are told that Lake Wakatipu is an example of crypto depression – meaning most of the lake bed is lower than sea level. Bus journeys like this, with wide tinted windows and an elevated view, an adventure ahead, with new companions, mean that new words and unusual geographic details such as this, raise laughter, banter, and generate a bond – our first ‘word of the day’ and it is never quite supplanted.

Our driver entertains us with the story of the lake’s making, the Maori myth of the giant Matau,who fell in love and absconded with a Chief’s daughter. Here he lies still, folded in the foetal position, after the local tribe took revenge on him and set fire to the ferns he slept upon. The fire is supposed to have created a whole in the ground the shape of an S (the sleeping Giant… with Queenstown at his knee) and to have melted all the snow and ice around, creating the lake. Each rise and fall of the lake is caused by the giant’s heartbeat we are told and we believe. Less than a week later, we hear that two young Frenchmen on kayaks who did not understand the force of his heartbeat were drowned in the rise and the fall of his breath.

The journey from Te Anau across the lake to begin our walk is poignant at the moment we pass a cross on a small island marking the spot where Quintin Mackinnon’s boat was found without him – the man who pioneered the Milford Track to the New Zealand public, instead of lost somewhere in a remote ravine, drowned somewhere in Lake Te Anau, his body was never found. The short journey we have taken from the jetty to here, illuminates for me how this could happen. I pour myself a cup of boiling tea from an urn and try to negotiate the ladder up to the top deck of the boat in spite of warnings from our guide. What might have been scalding water, bubbles and blows all over my hand on the open deck – but by the time the tea lands on my skin, it has already thankfully, cooled in the swiftly turbulent air. I barely taste tea, and instead watch as most of the content of the cup, mirror the surface of the lake we are crossing – and perhaps the sort of conditions in which Quintin Mackinnon was lost.

The walk to Glade House is a doddle. I feel invincible. My pack is a breeze and the lodge is less than 1.5 kilometres from where we’re dropped off. It’s disappointing too, because after sitting so long in the bus, so much anticipation, I’m ready to be challenged. We drop off our packs and take a short hike with our guides to a smallish waterfall and clamber on rocks to feast on fresh Fiordland-water that we scoop into our greedy hands.

</

</

In the morning we begin the real thing by crossing the Clinton River via a suspension bridge, just low enough not to terrify and wobbly enough to delight. From here we start following the river, heading into Beech Forest, treading the soft underlay of leafy carpet. There’s a small detour to a circular boardwalk that transports us into unspoiled Wetlands. Spread before me is my Granny’s Axminster autumn carpet, the forgive-all brightly coloured thick-pile of orange, brown, limes, greens and red.

Except this carpet is alive, and it’s brightest tiniest carnivore, a small red flower, is eating insects whole, as we watch and with our encouragement, hoping they are the infamous sand flies we are trying to avoid.  </

</

Hubby and I have doused ourselves in citronella and beeswax to foil the sand flies while others are relying on a more chemical solution. The guides spurn everything and tell us their bare legs are more or less immune now, after several seasons.

</

</

The Wetland leaves me tearful. I want to dance on the boardwalk and to sing, but it is early days and we are all, mostly strangers. And then we continue, out into the wide open along the old packhorse trail with perpendicular rock faces on either side of the valley. The Milford track is still pegged in miles, and as the four in our group are all baby boomers, we feel nostalgia. We think of Dick Whittington perhaps with his knapsack on his way to London seeking streets paved with gold, as we walk through this geographical wonderland paved with a different sort of gold.

There’s a poem to be written simply re-sounding words like, brown teal, tui, tom tits, riflemen, walking sticks, sphagnum moss, crown fern, granite, kidney fern, grass, glacier and bell rock. All around is the sound of the bush, the beech trees, and later on, the water falling, oh the water falling. How lucky are we to be hiking in early November after a long wet spell and the water is everywhere, but not at flood level and we spot two blue ducks in the river.

Evidently (according to our guide), there are only fifty breeding pair left in the world. We watch as they duck one another. I’m all grown up now and I know this is flirting and not fighting. I think they like the audience, and we’re impressed. Although they look less like blue and rather more like grey ducks on the blue water. And then, not that night but the very next we see a blue duck walk across the green grass, and he is cobalt, indigo, indescribable, and he or she knows it.

Ah, but that’s getting way ahead of myself, as we haven’t even ascended the Mackinnon Pass. We haven’t arrived at Pompolona Hut and like true amateurs, rushed for the hot scalding showers in our en-suite bedrooms, and then gone naked practically to wash our socks in the sun. The sand flies must laugh a lot at Pompolona Hut. They must chortle as they see us climb the last white boulders from the avalanche that blocked the Clinton river, all smothered in insect repellents, invincible and inedible. And they must congregate with stifled laughter in the bushes by the stainless steel basins, as we stand freshly showered, queuing to be eaten alive.

We discover a pianola at Pompolona and after dinner, and quite a lot of wine too, the mingling begins. The Japanese love their karaoke and the pianola as the hammers strike, the music plays and the words turn around on the paper roll, proves just as popular. We sing Bimbo possibly the silliest song ever written and we can see from the faces of our young guides that they cannot believe the words – and nor can we, and that we remember them!

Bimbo, Bimbo, where you gonna go-i-o somehow encapsulated our joy.

With a hole in his pants, and his knees stickin’ out, he’s just big enough to walk.

A silly, silly song, but our lungs are filled with joy and they spill with laughter, those of us old enough to remember the fifties.

What is it about the Milford Track? It is a rite of passage for Kiwis and I felt a sort of religious awe as I trod this well-trodden path from meadow to riverbed, through wetlands and up the granite face of Mt Mackinnon in the footlights of Mt Cook lilies.

Okay, so it was misty and damp on the ascent and we stood at Mackinnon’s Pass drinking our Miso soup, minus the much vaunted view. We peer from the 12-second drop vantage point, imagining. But we have sung Bimbo on every corner, counted every zig and zag, and our voices perhaps are still echoing down somewhere where a rock wren rests with his hands over his ears, fearing tinnitus perhaps.

Walking in the wilderness with friends and complete strangers, lends itself to random confidences, unusual encounters and unexpected intimacies. We marvel at the stamina of the tall rangy Japanese man who calls himself Cowboy who drank too much the night before, harassed us and then sung his heart out with us, as he now stops on one of the zigzags, to light a cigarette. Rice, we decide, it must be the healthy rice diet. And then later, after an especially triumphant chorus uphill, my companions confess that when they were first married, the husband, a tall intrepid Man Alone, sort of guy, used to sing Running Bear to his wife at night in bed, until she fell asleep. I see him tenderly, sweetly, curled, for he is far taller than she is, his voice softened and singing, and I see her, his ‘Little White Dove’ her small blonde head upon the pillow. And of course, this leads me to tell them that my husband (who now lags behind on another zigzag as he finds the next perfect photograph), used to tap out tunes on the back of his front teeth as if playing the piano and ask me to guess the tune. And, that I rarely guessed correctly, and that he rarely taps his teeth now.

Then, there is the young tourist with us, all pale skin and delightful red hair, with a whine in her voice and who is certain that this Milford tramp is far too hard for her and would like for the rest of us to share her very heavy pack contents, so that she can ascend Mackinnon Pass more easily. Before we depart she shakes an array of pills onto her breakfast plate to prove how ill she is. When she tells me her back hurts, I tell her to stretch and bend and get the spinal fluids moving. Our group are unmoved by her plight, she is far too beautiful and provocatively built, to need help with her pack. Plus we rationalise that she booked the trip and so she must have known, determined not to feel bad for turning our backs on her. Another far kinder fellow tourist weakens and tries to garner support from the rest of us, to spread the load. We feign indifference and allow her to be the martyr.

Pass Hut, at the top of Mackinnon Pass, is crowded with cold trampers, steaming breaths and walking poles. The loo with a view has a growing queue on the porch of the hut as it is far too cold to stand waiting by the toilet. Trampers who try either unwittingly or craftily to dodge the queue are castigated loudly and shamed until they return to shelter. One of our party loses his walking poles to an eager walker who departs early and there is confusion and consternation as everyone checks their own poles, making sure of ownership.

We are warned before even ascending Mackinnon’s Pass that the area is currently avalanche prone and we will have to descend via the emergency track. For the novices, this is disconcerting and afterwards, we urge the guides to consider renaming the route. We come up with original ideas such as the alternative route. It turns out to be the track used prior to the 1970’s and one whole kilometre (yes!) shorter than the new track. Of course it is steeper but with two trusty walking poles and a sturdy backside, it is worth it. The sun is re-emerging and groups of younger trampers are abandoning their packs on the track to scamper back up the hillside to catch the lost views from the top. We watch them envious of youth, but happy to keep descending.

I had vowed at the beginning of this day, that no matter how tired I felt after the descent to Quintin Lodge, I will embark on the extra one and a half hour return journey to see the Sutherland Falls. It would be so easy to simply drop your pack and sink into a sofa with a glass of wine. But instead, we barely pause for breath except to lift our packs from our backs and set off on the “short walk” (and that my friend is Guide-speak) to see the Falls. I was pretty much admiring of a nimble 71 year old Japanese mother-in-law travelling with her husband and daughter-in-law, wearing her low-cut practically trainers, as she leapt lightly from boulder to boulder, and passed me en route. And guilty too, as one of our group had purchased flash new tramping boots that hurt – and she’d decided to abandon them and only wear her trainers prior to leaving on this trip – and we had gang-pressed her into wearing her hurting boots – certain that trainers would not do the trick.

The Sutherland Falls are so abundantly full of water that we cannot get within cooee of them let alone attempt to walk behind them as I had imagined. The spray is spectacular and the sound of the falls like low flying bombers, if benevolent. It is impossible to take a photo close-up without drowning both the camera and the photographer. On the way back down we find a safe spot out of the spume in a clearing of meadow along a sidetrack. I promptly lie down and watch the sky like a child in a hammock of grass while hubby takes photographs.

Back at the lodge, I bump into the pale red-head who has just finished showering, her lovely hair all washed and wet and I ask her ‘How are you?’, she lifts her head slowly, as if to show that even her head is too heavy to hold and tells me “I’m alive”.

At the start of our hike, the first night at Glade House, we all stand up and introduce ourselves. Most people are hastily planning what they might say about themselves that they don’t really take in too much of what others are saying. But I am intrigued by a handsome English tourist who introduces not just himself, but his handsome wife who allows him to speak for her. She is one of those women; great posture, great profile, long greying hair coiled graciously and nice skin. My friend and I find it amusing to imagine allowing our husbands to speak for us. I comment to one of the men in our group, how beautiful this woman must ‘have been’ and he replies almost sharply as if to admonish me, ‘still is’. I’m fascinated, the way this woman commands attention, the same way the reluctant red-haired tramper encapsulates a certain pouting femininity that men seem to find attractive, a certain contrived helplessness in spite of an outward robustness. I compare (and oh, of course, I am generalising wildly here) the can-do, straight-forward, practical and resourceful Kiwi and Australian women walkers.

And in case you think me heartless, I must tell you, that on the very last 21 kilometre half marathon through bird-filled beech forest and the sounds of falling water, as I succumbed to extraordinary weariness, barely able to lift one foot in front of the other – I observed the red-haired invalid, practically sprinting, fresh-faced, radiant and shockingly youthful.

The whole journey has me casting my mind back to my upbringing and childhood as a young girl in the fifties in New Zealand. We had no car and we biked everywhere. Our parents didn’t mind that we vanished for the day to the river, or the beach, to swim or to fish, unsupervised. They applauded when we took off in the early morning light with a whitebait net over my brother’s head, me on the crossbar and the handle of the net facing forward, launching us. Down Beach Road we rode, towards the mudflats and just beyond the rubbish dump, to catch whitebait for breakfast, transporting them home in milk bottles. We leapt fences and private paddocks to collect mushrooms that Mum fried for us in a pan over the old coal range.

My friend and I walked for miles over the switchbacks in the pale summer grasses, and we climbed the blue hills in search of the reservoir (before we ever heard of Janet Frame). We played tennis in the evenings in the middle of the road outside our house; we rode to school three abreast, arms folded, and home again at lunch-time still talking; look, still no hands.

Except of course on Sundays; when having no car, was for me a source of deep melancholy, a sense of loss. My friends would vanish in the latest pastel Vauxhall with their families, their spades and buckets, and even over summer with their tents. I would languish on my front lawn alone, abandoned and certain they were having so much fun. Only years later did I learn how much my some of them loathed their Sunday drives, their forced family outings and that they envied me my solitude.

And so, at sixty, I have walked the Milford Track. I didn’t grow up with an outdoor family but I lived outdoors. We had a small house of a certain kind built in the fifties with a front room that was only used for visitors. People lived in their large kitchens but children lived outside until it was dark and their mother’s called them in, a chorus from street to street, under coal black and starry skies, the homecoming, like a flock of nesting birds, we returned, most often with unwashed feet to scamper into our beds. When we did wash our feet, it was in the kitchen sink.

The Milford Track reminded me of just how lucky I am, and how lucky I was.

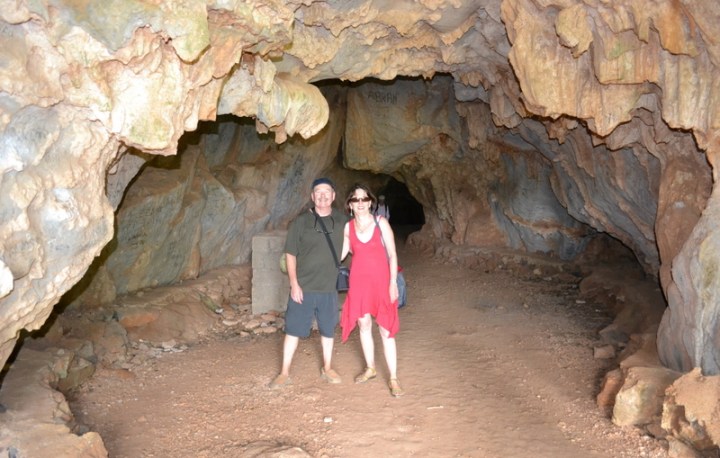

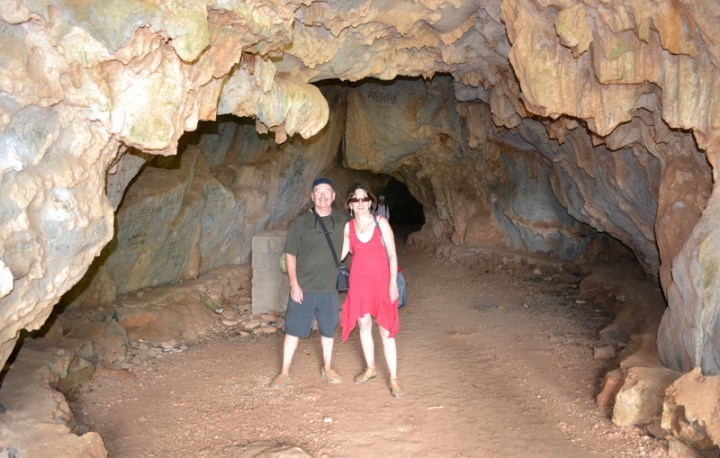

And here are some more of John’s great photographs –